China CSP

Provide Feedback

CloseShare With Contacts

CloseShare With Contacts

CloseCopy Link

Closehttps://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Delete Message?

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

An update is now available for this app!

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Modern China: global powerhouse, economic phenomenon, and for Australian businesses, a major opportunity.

Some key facts:

China presents unique challenges – including language and cultural barriers, bureaucratic corruption, lack of intellectual property (IP) law enforcement and quality control – but also immense potential rewards. The recently signed China Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA) will provide major new opportunities.

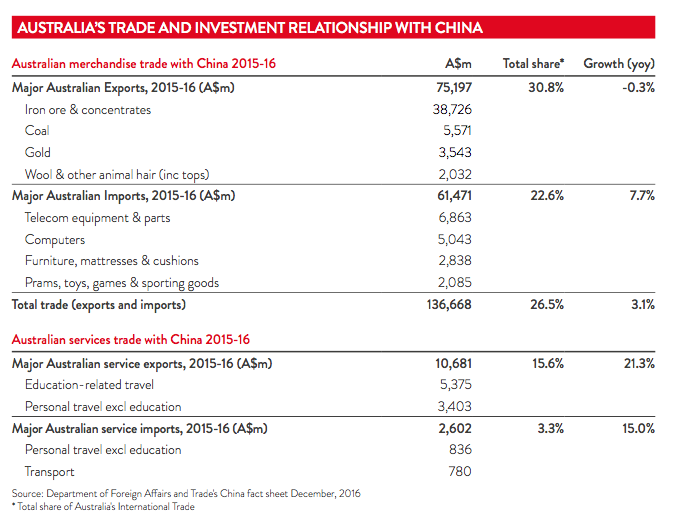

China has long been Australia's largest trading partner: trade between the countries reached almost $150 billion in 2015-16. While iron ore and coal make up the bulk of Australian exports to China, Australian service industries are a growing part of the trade relationship. China is the largest foreign buyer of Australian agriculture, forestry and fisheries products, while Australia's main imports from China are manufactured goods, led by telecommunication equipment, IT products, furniture and homewares.

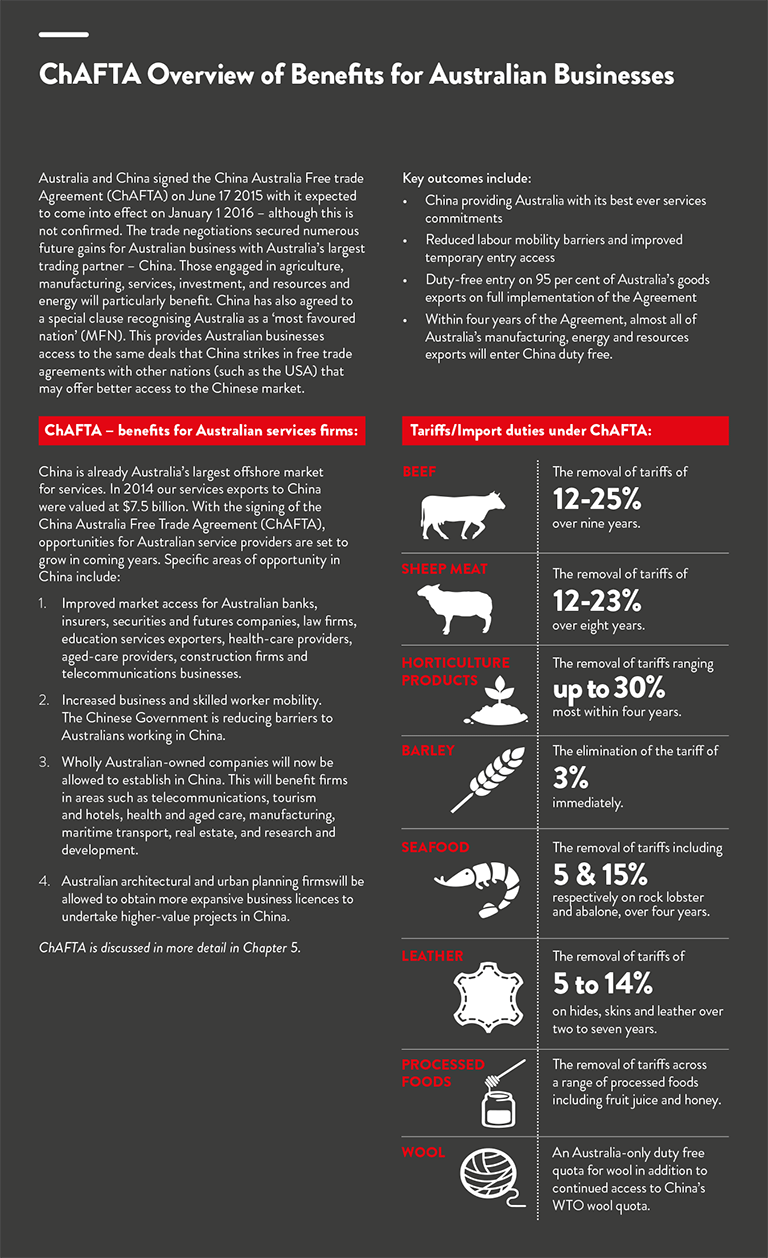

ChAFTA means Australian financial and legal firms can now do business in China for the first time, and many other services industries can set up wholly -owned Australian subsidiaries there. Tariff reductions will benefit many businesses.

The resources sector is likely to dominate Australia's trade relationship with China for a long time to come, but other sectors offer opportunities:

Education: Chinese parents are increasingly choosing to send their children abroad for secondary education, in preparation for foreign university.

Tourism: China is Australia's second-largest inbound tourist market (measured by arrivals), and the largest when measured by tourism expenditure.

Aged care: The Government plans to provide seven to eight million beds by 2020. ChAFTA permits wholly Australian-owned hospitals and aged-care institutions to be established in China.

Financial services and investment: As Chinese incomes rise, more people need banking, insurance, investment products, financial planning and other consultancy services.

Legal services: Under ChAFTA, Australian law firms will be the first foreign entrants able to establish commercial associations with Chinese law firms in China, specifically in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone (SFTZ).

Information communication technology (ICT): E-commerce has fuelled an explosion in internet connections across China. There are more than 600 million internet users. The Chinese Government's target is to connect 1.2 billion people to 3G or 4G mobile internet by 2020.

Agriculture and processed food: China buys more Australian agricultural produce than any other country.

Infrastructure development: China needs more efficient buildings, more sustainable energy use, help to transition from fossil fuels to less environmentally harmful sources of energy, and new transport infrastructure.

Another reason to consider China: It is a global business and transport hub, providing access to some of the world's largest markets. It has 12 free trade agreements in force and several more under negotiation.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

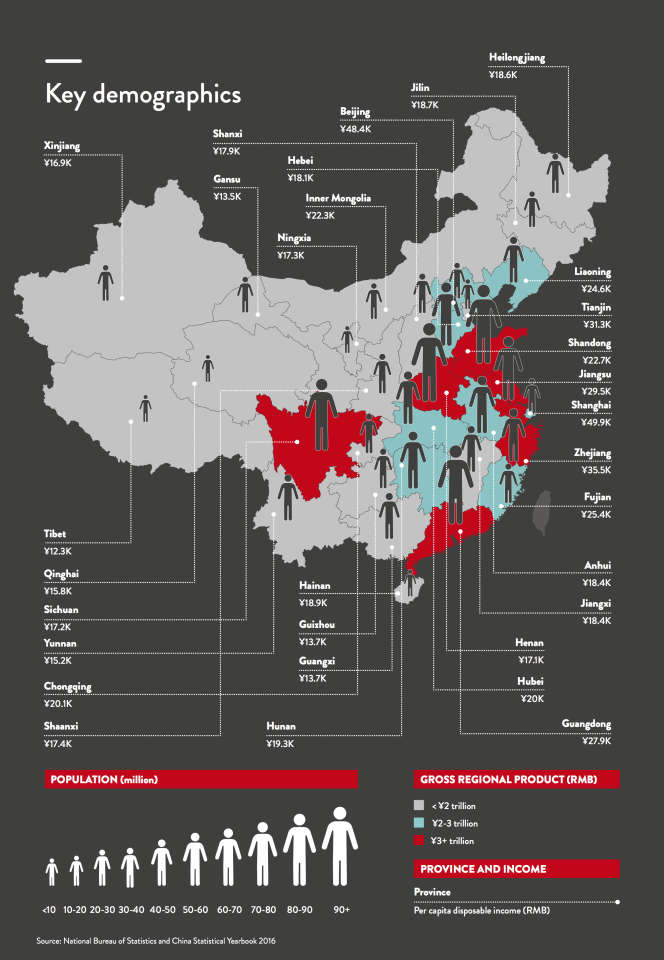

China is the world's fourth-largest country, covering about 9.6 million square kilometres. Its geography and climate are highly diverse. There is a monsoon season in the south from April to October, and typhoons along the southern and eastern coasts between May and November. More northern regions experience four distinct seasons.

Greater China includes a number of other high-profile regions in addition to the mainland: Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Hong Kong and Macau are classified by Beijing as Special Administrative Regions. What is now known as Hong Kong was leased to Britain from 1898 to 1997, when ownership returned to China. Hong Kong has its own currency, government, customs territory and legal system. There have been recent tensions in regards to Chinese control of Hong Kong, highlighted by the 2014 'Umbrella Revolution' protests over electoral reform.

Former Portuguese colony Macau returned to official Chinese control in 1999. Its constitution stipulates that its social and economic systems, lifestyle, rights and freedoms are to remain unchanged until at least 2049. It has a separate currency, legal system and customs territory.

The status of Taiwan is somewhat sensitive in China. Australia adheres to Beijing's One-China Policy, and does not have formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan. Australia does maintain unofficial contacts with Taiwan promoting economic, trade and cultural interests and encourages Australian businesses to pursue investment and trade opportunities in both the People's Republic of China and Taiwan.

*Hong Kong and Taiwan will be examined separately in individual guides. This guide specifically focuses on mainland China, including the island of Hainan.

For more on China's history, see (website).

China has dozens of different ethnic groups. The largest is the Han people at under 1.3 billion, with the others accounting for approximately 100 million people combined. Tibetans, Mongolians, Uighurs and Zhuang are the largest minority groups.

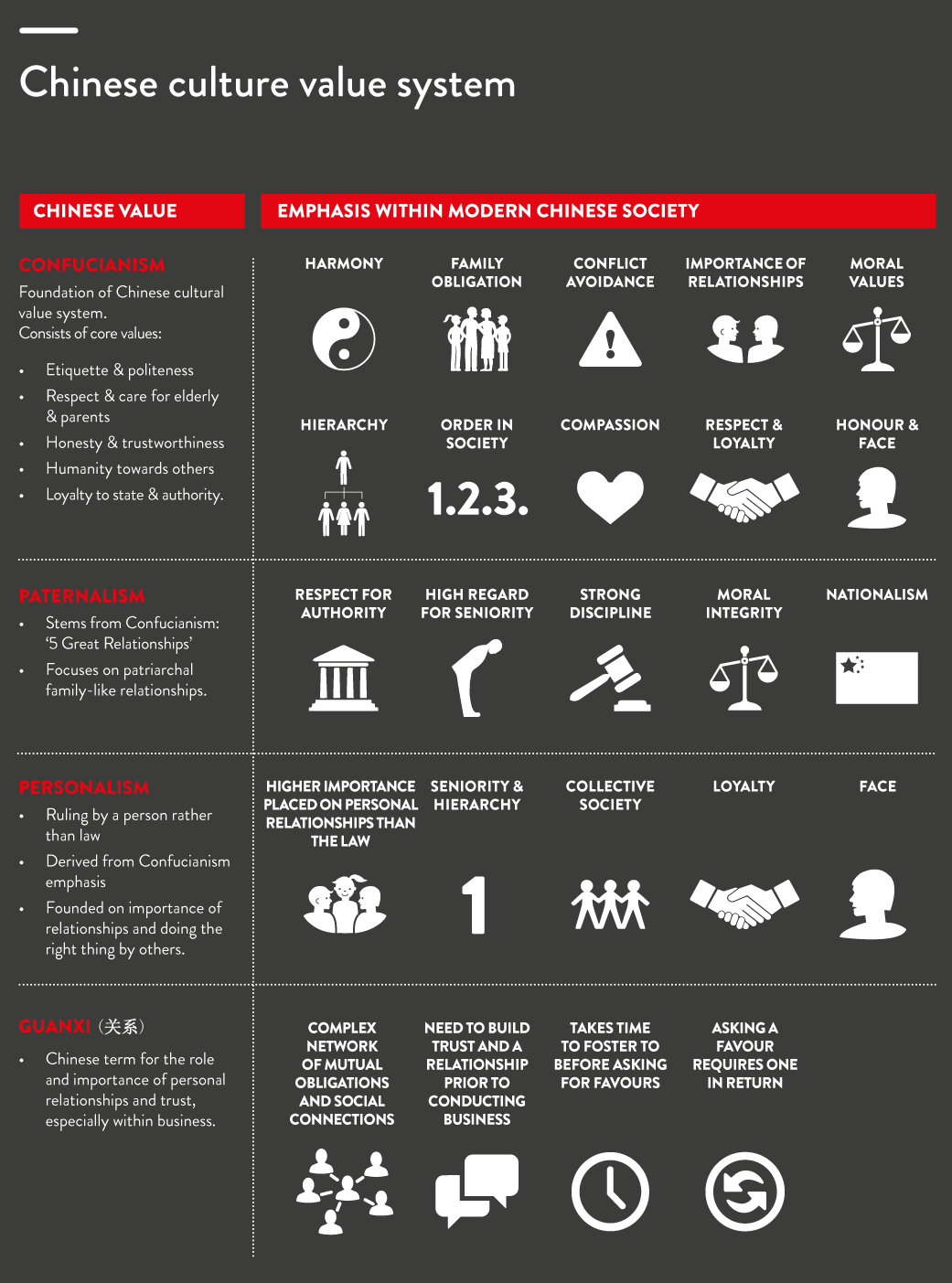

The primary core value of Chinese culture is founded on Confucianism – the teachings of the philosopher Confucius, who lived some 2,500 years ago. From this stems the strong emphasis in China placed on relationships, family, hierarchy, nationalism and the importance of 'face'.

In business relationships, you may be asked to share personal information – how much you earn, or what your religion is. It is all about what the Chinese call guanxi (关系). It can involve moral obligations and exchanging favours, and is sometimes incorrectly perceived in Western business as bordering on corruption. See Chapter 4 for more.

Chinese people aim to preserve a harmonious environment in which a person's mianzi – face – along with their social standing and reputation, can be upheld. Accept the need for slow, consensual decision-making and relationship-building. Contradicting someone openly, criticising them in front of others or patronising them will result in diulian – loss of face.

Today 46 per cent of the Chinese workforce and a quarter of entrepreneurs are female. It's acceptable for mothers to work, with grandparents caring for the children. The one-child policy has curtailed population growth, but may also have created indulged single children and a low birth rate that threatens long-term economic growth. The Government announced in October 2015 a change in the one-child policy to allow married couples to have two children for the first time in more than three decades. However, only 50 to 60 per cent of the one-child generation say they want second children because of the high cost of raising them and the desire for a higher living standard.

The “iron rice bowl", where state-owned enterprises would provide employees with lifelong employment and support such as meals, schools and housing, is in decline – although can still be found among older generations.

During the Cultural Revolution major religions were effectively banned. Today, there is a policy of freedom of religious belief, although the level of religious observance is unclear. Religious people and non-believers live in harmony and the primary sources of values remain traditional Chinese culture and Confucian thought.

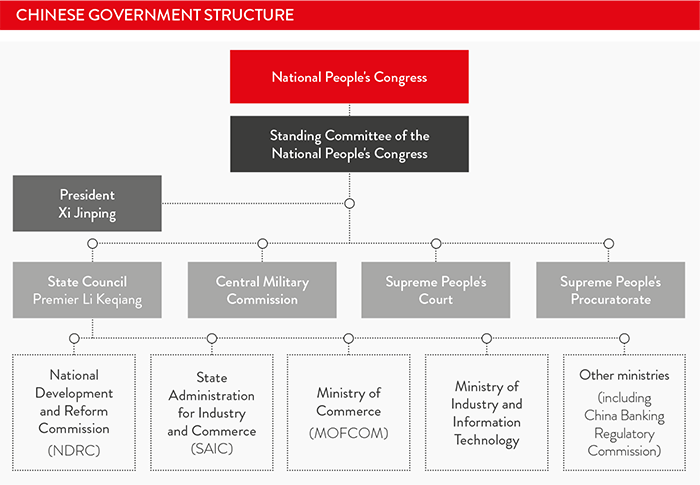

Understanding the workings of the Chinese central government is essential to understand China's business culture. While this section details government at a national level, businesses seeking to operate in China should also have some awareness of the roles of provincial and municipal levels of government.

The CCP was founded in Shanghai in 1921. In 1949, after winning the Chinese Civil War, Mao Zedong announced the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The Communist Party has ruled continuously ever since, with a claimed membership of over 85 million people.

The Communist Party is the overarching political authority in China, headed by the General Secretary (or President) – a role held by Xi Jinping since March 2013. China's military, the People's Liberation Army (PLA), is also directly under Communist Party oversight and overseen by China's Central Military Commission.

The President: Chinese presidents serve five-year terms, for a maximum of two terms.State Council: The administrator and regulator of China's day-to-day government functions, comprising ministries, bureaus, commissions and agencies. Headed by Premier Li Keqiang.

Political Bureau (Politburo): The Standing Committee of the Politburo is China's most powerful political entity. It effectively controls the direction and pace of China's economic development.

Central Committee of the Communist Party: The Communist Party takes its direction from policies devised by the highest governing body in China, the Central Committee of the Communist Party, which is further guided by the Standing Committee of the Politburo.

National People's Congress: China's parliament. It debates and ratifies the policies set by the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Politburo, ratifies laws and has oversight and appointment authority for the State Council and courts. Elected for five-year terms and meets annually.

Plenums are meetings of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee, usually held annually. The First Plenum introduces the new leadership, the Second tends to be personnel- and Party construction-focused, while the Third is usually where the new leadership introduces its economic and political agenda. The Fourth Plenum in 2014 focused on the Chinese government dedication to following 'rule of law' in order to continue China's economic growth.

Five-year plans indicate how China's economic, social, environmental, geographic and legal landscape is likely to evolve over the coming five years. Neither a law nor a regulation, the Five-Year Plan serves as a road map of government priorities and interests. 13th Five Year Plan covers 2016-2020. It places a significant focus on growing domestic consumption, introducing structural reforms such as financial and investment regulations, and enhancing social welfare, introducing various health care reforms.

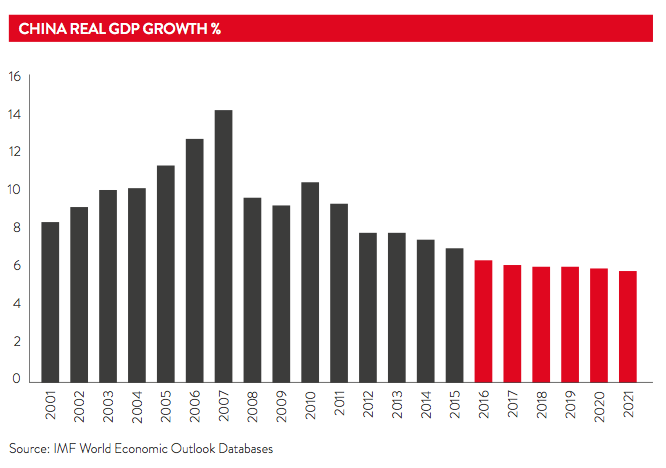

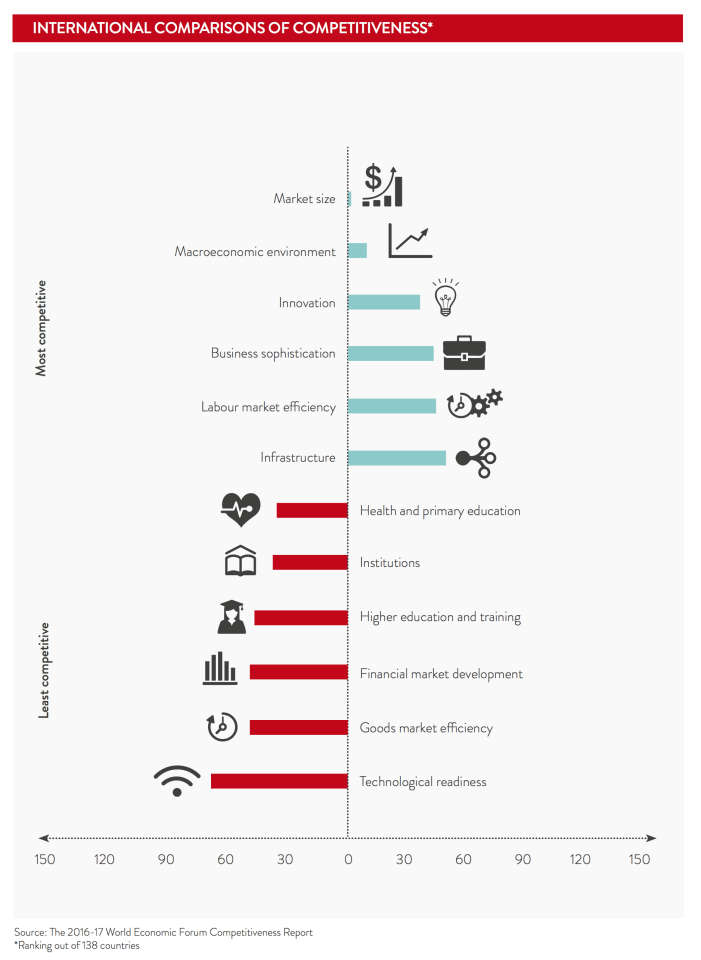

China's economy is the second-largest in the world, behind the US. It has slowed after three decades of spectacular growth, but is still growing faster than most other major economies. Growth took off in 1978, when leader Deng Xiaoping began market-based reforms. The size of the Chinese economy grew by roughly 48 times, from US$168.367 billion (current prices) in 1981 to US$11,38 trillion in 2015.

China's “socialist market economy" sees a dominant state-owned enterprises sector exist alongside market capitalism and private ownership. Private businesses now produce more than half of China's GDP, most of its exports, and most new jobs, although state-owned enterprises remain important.

There are large wealth imbalances between China's rural and urban populations. The eastern provinces are the wealthiest, agriculture-focused Central China less so, and Western China the least prosperous region, although it has significant natural resources. Economic growth is now becoming increasingly reliant on domestic consumption.

While cost rationalisation is still an attractive feature of the China market, global and local businesses are now starting to change strategies to tap China as an engine for growth. Approximately one-third of global business leaders rank China among their top three regions for generating growth over the next year.

Manufacturing: Manufacturing accounted for 40.9 per cent of GDP in 2015 and employs about 28 per cent of workers in China. The focus on the more developed eastern coast is increasingly on advanced manufacturing, with lower-cost and more labour-intensive manufacturing further inland.

Services sector: China's services sector has doubled in size over the past two decades and accounts for about 50.7 per cent of GDP and 38 per cent of workers. Major industries within the sector include transport, storage and post (five per cent of GDP), wholesale and retail trades (10 per cent), hotel and catering services (two per cent), financial services and real estate (six per cent each). Despite spectacular growth, its share of GDP in China remains much lower than countries such as Australia (68.2 per cent) and the US (79.5 per cent).

Agriculture: China is the world's largest producer of agricultural products – ranking first for products including rice, wheat and potatoes. Today the sector accounts for 9.7 per cent of Chinese GDP, but employs 28.3 per cent of the labour force – close to 300 million people.

The Chinese legal system, one of the world's oldest, is primarily based on civil law. It presents challenges for foreign businesses.

In common law jurisdictions, such as Australia, court judgments are generally binding. But Chinese law combines national laws and national and local regulations, supplemented by court interpretations, departmental notices and local practice. Different interpretations of the same regulations are often applied.

For more on China's legal system, see (website).

Infrastructure investment in China has driven economic growth and improved living standards, but there is still a shortfall. The Government has pledged to accelerate 300 projects valued at RMB seven trillion ($1.28 trillion), which they hope will help shore up China's annual GDP growth amid indications that it is set to slip below seven per cent.

Much recent infrastructure development has been focused around major east coast urban centres.

Transportation has attracted about a quarter of total infrastructure investment, with much going into roads. China's highways and expressways expanded from one million kilometres in 1990 to more than 4.3 million kilometres today, but only 54 per cent of roads across the nation are paved. A National Trunk Highway System links all provincial capitals and cities with populations of more than 200,000. About 70 per cent of the system is expressways.

China's rail networks have been expanded and modernised. Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen have the biggest urban rail systems. New lines are being constructed in the biggest cities and other metropolitan areas along the eastern seaboard.

China has the world's biggest passenger-dedicated high-speed rail network at 12,000 kilometres, and more lines being built and upgraded. It's also at one end of the world's longest railway link, which carries freight trains the 13,000 kilometres from Zhejiang province to Madrid, Spain. It takes 21 days to get freight from China to Spain via 'The Silk Railway', but six weeks by sea.

China has about 200 ports and container terminals, including 34 major ports engaged directly in international trade. Six are ranked among the world's 10 busiest, including the number one – Shanghai.

China's air transport infrastructure is expanding rapidly. It has around 200 civilian airports (excluding Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan) with more than 100 million Chinese travelling overseas in 2014. The Government plans to increase the number of civil airports to 244 before 2020. The top five airports in China in 2015 each serviced at least 39 million passengers.

Modern telecommunication facilities are available across most of China. There are more than 900 million telephone connections, including some 641 million mobile and 340 million fixed-line subscribers. Eastern seaboard provinces have almost half of China's telecom users.

About 52 per cent of the population, or more than 710 million people, were believed to be connected in 2016. By the end of February 2017, the total number of mobile broadband users in China reached 978 million. China Telecom, the state-owned and largest telco in China, has built a nationwide 3G network covering all cities and more than 96 per cent of villages and towns. It has also established the world's largest optical fibre network, spanning more than 83,000 kilometres.

China's online censorship system, commonly known as 'the Great Firewall', blocks social media sites including Twitter, Facebook and YouTube, and numerous foreign sites. It allows the Government to monitor internet usage, but more people are trying to circumvent it with virtual private networks (VPNs). Hong Kong is becoming a popular cloud computing hub because it is beyond the jurisdiction of the censorship system.

Water and sanitation is an area of China's infrastructure that is advancing, however, can be challenging in more remote areas. The World Bank (2015) estimates that 95.5 per cent ofChina's population has access to improved water sources, however, only 76.5 per cent have access to improved sanitation facilities.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

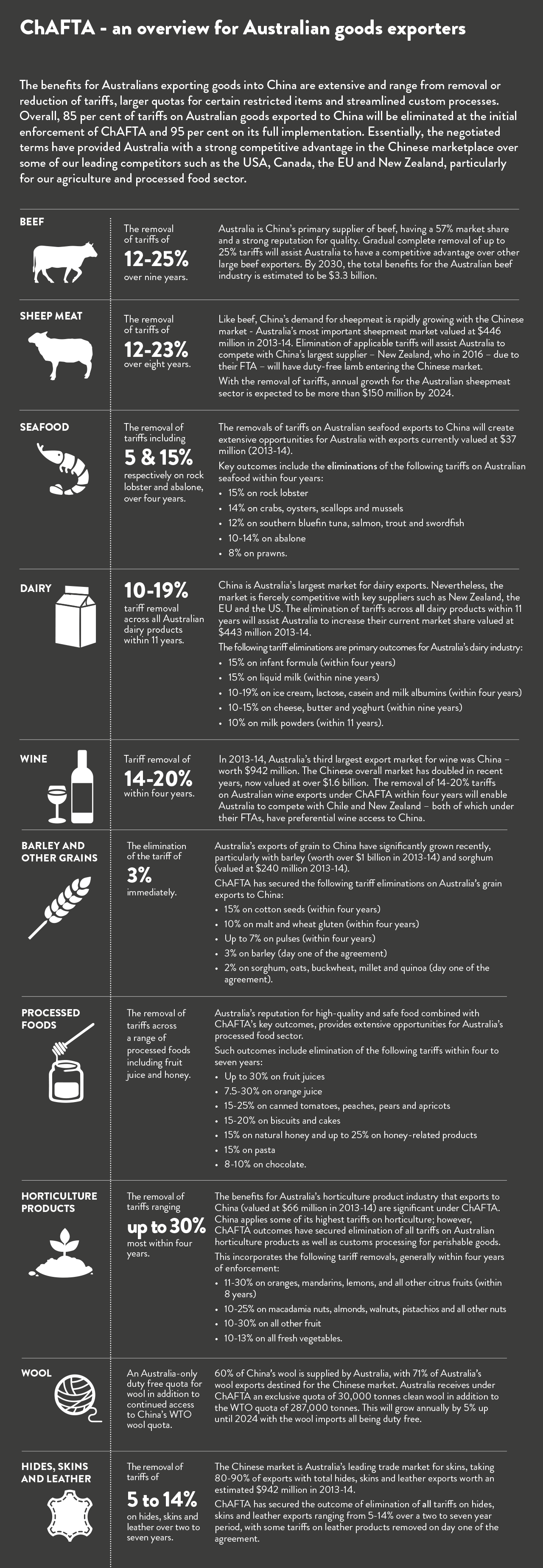

Two-way trade in goods and services in 2015-16 reached just under AUD 150 billion, with Australia buying roughly AUD 61 billion in merchandise (mostly manufactured) imports from China and the Chinese spending about AUD 75 billion on Australian exports (goods).

Thanks to the rise of the Chinese urban middle-class, Australia is finding growing markets for its agricultural produce, processed food, tourism, education, more specialised professional services and advanced manufacturing. These opportunities could be an economic cushion against the end of the mining boom.

Although China's growth will inevitably slow as its economy matures, Chinese GDP is still expected to grow at an extraordinary (by Western standards) five to seven per cent in coming years.

Successive governments in Canberra and Beijing have worked hard to build and sustain the bilateral political relationship, despite differences in opinion – particularly on human rights and the Tibet Autonomous Region.

The entry into force of ChAFTA demonstrates the potential value of constructive collaboration between governments that do not always see eye-to-eye and provides new opportunities to rebalance our exports to China.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

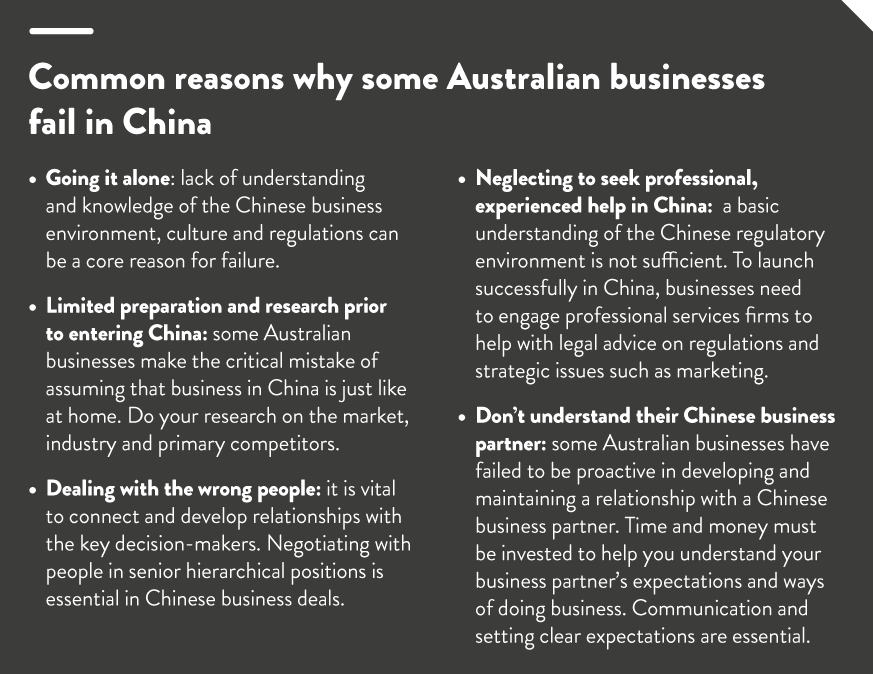

Your first step should be lots of research.

Careful planning is crucial: Be fully prepared before investing. The reality of China is often more complex than you expect. Effective due diligence is crucial (see Chapter 3).

Fully assess your markets and risk: Get to know your customers, partners, government contact points and stakeholders. Examine every level of risk, throughout all business functions.

Find appropriate business partners: Do they have enough local experience? Their resources and relationships should complement yours.

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Doing business in China may seem daunting, but taking a strategic approach can make the process manageable. In particular:

China is not a single market. Profound differences can exist from region to region, from industry to industry, and market to market. The most successful foreign companies in China are flexible, and adapt quickly.

Your choice of location is critical. Different locations and regions are becoming increasingly specialised. For example, Beijing has become a hub for IT companies and software development, whereas Qingdao is increasingly becoming a financial centre.

The eastern seaboard generally has the best infrastructure but also relatively high labour costs. Costs can be lower inland but there can be issues with shortages in supply chain and management talent, inconsistent infrastructure, fragmented distribution systems, and limited technology.

Consider location-specific government incentives and regulations. The Chinese Government has given high priority to developing rural infrastructure, and will invest more in areas with ethnic minorities, in border regions and other underdeveloped locations.

China suffers skills shortages across various sectors and regions. In certain industries there are also restrictions on the employment of expatriates, which can add to the challenge of finding experienced, skilled workers.

The central and provincial governments have launched a variety of free trade zones, special economic zones, export processing zones and technology development zones, where foreign businesses receive various administrative and trade incentives. Check with your Australian state trade office to see if your state or city has a relationship with a special trade zone in China.

The Shanghai Free Trade Zone (FTZ) is of particular interest. This zone is listed in ChAFTA as a key area for innovative and liberalised Australia-China cooperation. The Chinese Government is using it to trial policies and regulations that encourage administrative innovation, and stimulate trade and investment. Three more FTZs were opened in 2015, in Tianjin city, Guangdong province and Fujian province.

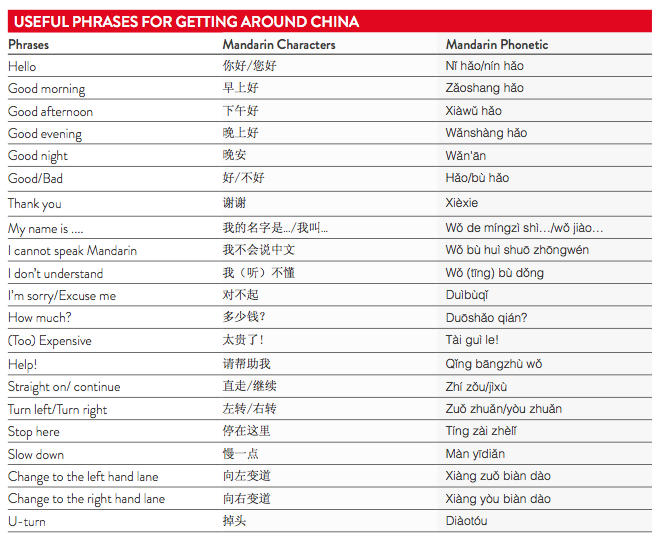

The official language of China is Mandarin (otherwise known as pǔ tōng huà - 普通话), but for many Chinese, their native tongue is their local dialect. Many (particularly younger) business people have studied English but it is not widely spoken among the general population in smaller cities and rural areas. Interpreters can be useful during business visits, particularly when you need to discuss technical issues. Many Australian businesses hire bilingual Chinese staff to attend meetings and negotiations, and increasing numbers of Australian business people speak Mandarin. You should at least learn basic phrases.

If you decide to hire an interpreter, make sure that:

Translators: Interpreters are for oral interpreting and translators are for written translation. Although many people have both skills, some specialise in one discipline.

Finding an interpreter or translator: The best way is to rely on the recommendation of someone you trust who has used them before.

What it costs: Costs will depend on the nature, duration and location of the meeting. Interpreters charge for a minimum of half a day. In Beijing or Shanghai, expect to pay between $700 and $1,200 per day.

Additional costs associated with conducting business overseas may include:

A wide range of funding options exists, with various grants, venture capital and equity sharing deals increasingly commonplace. However, banks remain the easiest and most approachable source of funding. Start with your existing bank manager.

Venture capital could be an attractive option if you are comfortable with a third party taking an equity stake – and a share of the profits – in your business. Learn more from the Australian Private Equity and Venture Capital Association Limited: www.avcal.com.au.

Government assistance – both federal and state – is available to Australian businesses wanting to expand overseas, especially exporters, through a number of grants, loan facilities and reimbursement schemes. These include Export Finance Insurance Corporation (Efic) – the Australian government's export credit agency (www.efic.gov.au) and the Export Market Development Grants (EMDG) scheme, administered by Austrade (www.austrade.gov.au/EMDG).

Individual state and territory government websites also contain information on what financial assistance they can offer. Other potential sources of finance include:

Going offshore entails increased risks. Due diligence must be actively practised.

Before entering the market, you'll need to understand China's distinctive banking, taxation and legal systems. Take professional advice and thoroughly investigate the risks – the information here is just an overview. Australia's Export Finance and Insurance Corporation (Efic) highlights China's key risks as:

While corruption is a significant concern, the Chinese Government is actively focusing on improving transparency and due diligence across government and business. China's sovereign risk is considered reasonably low, with a credit rating of AA-/Stable from Standard & Poor'

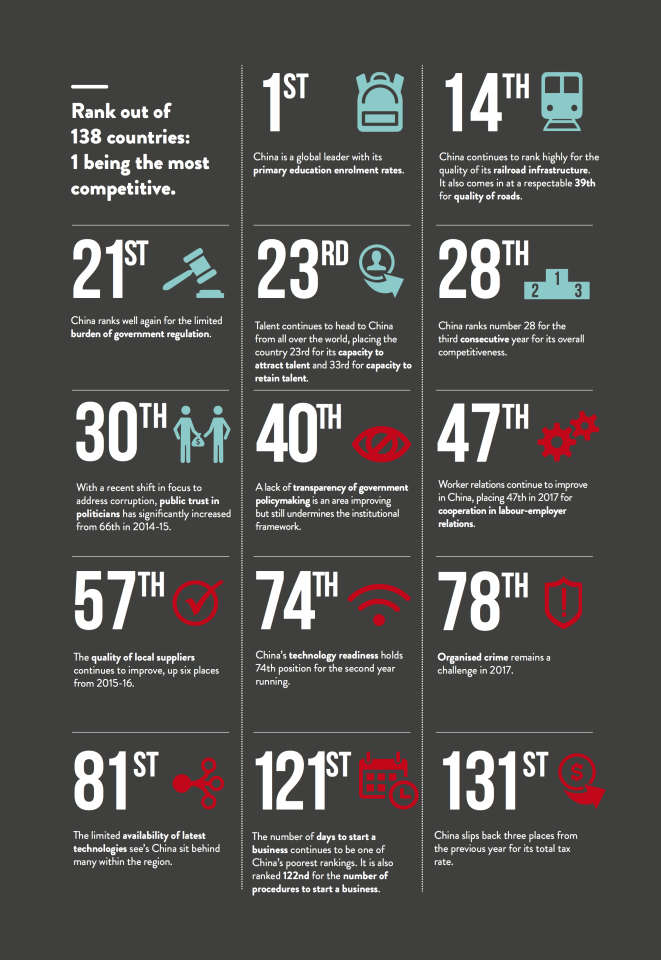

The World Bank's 2015 Doing Business Report ranked China 128th out of 189 countries (1 being the best) for starting a small to medium-size business, but 90th for doing business overall.

Intellectual property (IP) rights have been notoriously difficult to enforce in China. Despite recent improvements in the ability to both register and protect IP, some companies continue to suffer commercial losses due to problems in this area. See section 5.1 for more.

China's relationship with Japan is at times difficult due to historical grievances and an ongoing territorial dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. It's best not to discuss this with Chinese business partners. Protests over this or other local tensions are unlikely to target Australians or Australian businesses, but can be disruptive.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Comprehensive research is crucial when entering the Chinese market. Your research should go beyond this guide and cover a very wide field, from import duties and other regulations to market-specific issues such as distribution channels, market size and growth, competition, demographics and local production.

Consider the different geographies and markets within China: customer preferences, as well as regulatory and value chain considerations, vary.

Think about commissioning your own professional China-based research, and visit in person numerous times. Data availability and reliability can be problematic: market statistics might be region-specific, industry-specific, too broad or out-of-date to be useful, and much useful information may be in Mandarin.

Numerous research organisations in China, including large international professional and accounting firms can be a major source of information. Austrade provides a range of services for Australian firms seeking to go offshore, including:

The Queensland, South Australian, Tasmanian, New South Wales, Victorian and Western Australian state governments have representative offices throughout China and may be able to assist. The Australian Government's Export Market Development Grant (EMDG) scheme can help meet these costs and state and territory governments may provide grants too.

You will need to visit China to confirm the results of your research, develop a deeper understanding of potential markets, establish relationships and eventually negotiate contracts and agreements.

Determine where and when to visit: Go before entering into any agreements with prospective agents, distributors or other business partners. Consider meeting with several for comparison. Leave the most prospective contact until last, when you have a better understanding of the market and standards and are more prepared to handle questions and strategic options. Concentrate on only one or two markets at first to ensure a much better chance of success.

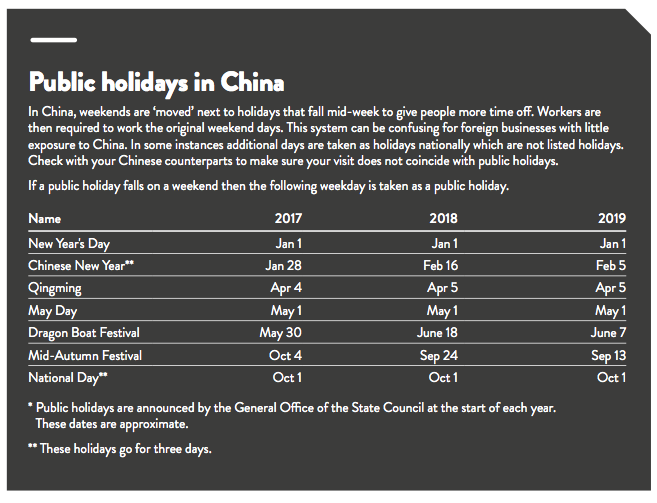

Plan your trip at least six weeks in advance: Arrange in-country assistance with planning your program to ensure you see the people, who will be briefed and screened for interest and suitability. Take note of holidays and religious festivals that occur during your planned visit. Have all your required paperwork completed before departing for China, and take with you any necessary legal documentation, company and product information and business cards.

Do some background reading: Do research on the internet, read news articles and travel books. This will help you ask better-informed questions.

Trade shows and exhibitions: These are a great way to meet potential customers or business partners. Arrange appointments to meet pre-identified contacts at events. Austrade and state governments organise regular trade missions to China. Check with your state government for details.

Don't waste valuable time in China doing what you can do in Australia. Various organisations have training courses or seminars that can expand your knowledge about doing business in China, including Asialink Business, Austrade, Export Council of Australia (ECA) and state and territory governments. These can give you access to networks and China experts before entering the market.

Prearrange as many of your meetings as possible and reconfirm them one day in advance. Research the people you are meeting with. Within 48 hours of your appointment, send an email thanking your contact for the meeting and providing any follow-up information. This will leave a good impression.

Many Australian cities have sister-city relationships in China which offer networking events and a network of existing relationships. Some have representative offices in China. Check with your local government for more details.

Joining a business association, such as AustCham, is a great way to learn more about what is going on in the local business community. The major cities have several well-established country-specific business associations. See the Resources and Contacts section for further information.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

No single business structure holds the key to unlocking the China market. Cultivating a wide network of local contacts in government, while gaining an understanding of local practices, will help lower your compliance risks and help you choose the most appropriate structure.

Setting up a business in China generally takes three to six months and, depending on your industry and chosen structure, involves various government authorities:

The four primary options Australians businesses can choose from to set up a foreign investment enterprise (FIE) are: representative offices (RO), wholly foreign-owned enterprises (WFOE), joint ventures (JVs) – of which there are two types – one being foreign invested partnerships (FIP).

Define your business scope clearly early, as it is what will appear on your Chinese business licence. Your business can conduct activities in China only within its business scope. Further approval is required if you want to change it.

Registered capital is the initial investment in the new business required to fund the operation until it is in a position to fund itself. The official requirements vary depending on the industry and region.

This is the easiest and simplest type of business structure to establish in China, popular with Australian businesses that simply want to get a feel for the Chinese market and make business connections. There are no registered capital requirements for an RO, but an RO cannot engage in any remuneration or profit-making activities, nor issue receipts or accept payment for services. It can only undertake market research and public relations activities relating directly to the business's products or services, as well as contact activities that relate to provision of the product and domestic procurement and investment.

In addition:

The Chinese Government has adopted stricter measures to stop foreign businesses abusing the RO non-profit requirement, including new taxation rules.

To establish an RO, the parent company must first apply to the SAIC for a business licence, then register with other relevant authorities. In certain industry sectors, approval from relevant authorities is required prior to submitting the SAIC application. The SAIC registration process generally takes between three and four months. Consider engaging a consulting company with more in-depth procedural knowledge to submit the application.

All applications must be submitted in Mandarin and additionally can be written in English. Approval permits are usually issued within one month of application.

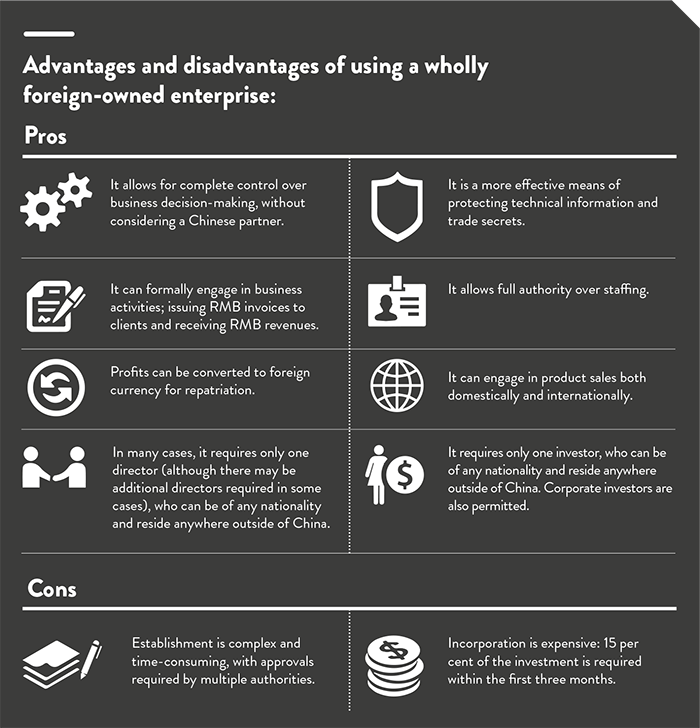

A wholly foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE) is a limited liability company entirely funded by one or more foreign entities. It's the most popular business structure with foreign investors as it permits the most freedom. A large amount of capital is required to establish a WFOE but it creates an independent legal entity that can engage in profit-making business, and manage the business in its own way while also allowed to create subsidiaries. A business license is usually issued for 30 years. Shorter or longer terms and extensions are possible.

The business scope and total investment must be accurately defined at the initial application phase to receive government approval as, once established, the WFOE is legally obliged to remain within the parameters of its business scope and meet its financial commitments.

Establishing a WFOE takes three to four months. An office space must be leased before beginning the application process; add a clause to the lease voiding the contract without penalty should the WFOE application be rejected.

The WFOE's investors must pay 15 per cent of the registered capital within three months of the business licence being issued, and the balance within two years. The minimum legal requirement is RMB30,000 if the WFOE has two or more investors, or RMB100,000 if the it has only one. Authorities will assess on a case-by-case basis the amount of registered capital, taking into consideration the proposed business activities and location.

A joint venture (JV) is created through a partnership between foreign and Chinese investors, who share the profits, losses and management of the venture. There are two major reasons for choosing to establish a JV: government requirements for specific industries, and the local partner being able to assist with market knowledge or established networks. It's wise to consult with the foreign partner of an existing JV to better understand the advantages and disadvantages of the structure. Exercise due diligence in choosing the right partner. See Chapter 4 for further information on due diligence.

There are two types of joint ventures in China – equity joint ventures and cooperative or contractual joint ventures, which differ predominantly in the ways in which profits and losses are distributed. JVs must pay 15 per cent of the registered capital of the venture within three months of the business licence being issued, with the balance due within two years. The same minimum investment requirements and consideration by the Government apply to JVs as WFOEs.

An equity joint venture (EJV) is the second most common structure used by foreign companies to enter China and the preferred vehicle of the Chinese Government and Chinese businesses. EJVs are usually established to exploit the market knowledge, preferential market treatment and manufacturing capability of the Chinese side, and the technology, manufacturing know-how and marketing experience of the foreign partner. They can last between 30 and 50 years.

The key attributes of an EJV are:

In a CJV there is no minimum foreign contribution required to initiate the venture. Investors' contributions can be 'in kind' support such as labour, resources and services. Profit and returns are divided according to the contract. A CJV also allows greater flexibility in the structure of the organisation, management and assets. There is a duration limit for CJVs, although contracts may be renewed subject to the consent of the parties involved and approval from the examination and approval authorities. The foreign investor is also permitted to withdraw all or a portion of their registered capital from the CJV during the duration of the CJV contract.

Foreign-invested joint stock companies (otherwise known as foreign-invested companies limited by shares) are rare in China and tend to be for larger organisations. The recently introduced foreign-invested partnership or FIP (otherwise referred to as a general partnership or limited partnership) has different benefits not offered by WFOE, including a set-up process without registered capital verification, tax savings, the options of domestic and foreign ownership (both corporate and individual) and hiring of foreigners. The challenge with FIPs is the unlimited liability of the general partner.

Another option for setting up in China is to establish holding companies for their Chinese entities in Hong Kong or Singapore, partially avoiding China's regulatory environment and giving a layer of protection between the parent company and Chinese subsidiary from potential risks and liabilities. Benefits include:

It takes 11 procedures to establish a corporate entity in China and an average of 31 days to complete.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

China remains the world's largest manufacturer, but increasingly, businesses are choosing to manufacture in China to service the growing Chinese market, rather than for export.

Contract manufacturing is a popular option, and Australian businesses can also invest directly in a Chinese factory. For more information on setting up a business in China, see section 2.3.

On the more developed eastern seaboard, where wages are higher, the Government encourages investment in high-end, low-polluting manufacturing. Further inland, more labour-intensive manufacturing is favoured.

There have been high-profile cases in which poor quality control by Chinese manufacturers has caused significant problems for international brands. Have robust quality control mechanisms in place and perform due diligence. See Chapter 4 for more.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

There are many options for getting your products marketed, distributed and sold in the Chinese market. Be sure to conduct due diligence and careful research, beyond this guide, into the marketing and sales strategies to suit your objectives.

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Most Australian firms rely on agents or distributors to represent their businesses and sell their products in international markets. The information here is general – make sure the role of the Chinese party is clearly defined in the contract.

Agent: An agent represents the supplier, but does not take ownership of the goods. They generally earn a commission based on an agreed percentage of sales value generated. Usually China-based, they often represent numerous services or product lines, operating as the sole agent for a company's goods or services in that market, or as one of a number of agents.

Distributor: A distributor buys the goods and resells them to retailers or consumers, and sometimes other wholesalers, earning by adding a margin to product prices. These are generally higher than agent fees because distributors have larger costs, such as for storage. They may carry complementary and competing lines and usually offer after-sales service. Chinese distributors rarely take on marketing.

Choosing an agent or distributor: The most important thing is that you can establish a close working relationship. Meet with a potential partner to get to know them better and observe their knowledge and presence in their own market. Get trade references and consider professional credit checks.

Consider:

Large agents and distributors sometimes manage so many products that yours may not get enough attention. You may need several agents to cover different areas. Remember, payments can only be repatriated easily if the goods were imported. If they are China-produced, agents can only repay funds after end-of-year tax has been paid.

There are no laws or regulations covering agents and distributors in China so make sure you have watertight contracts in place.

Contracts should:

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

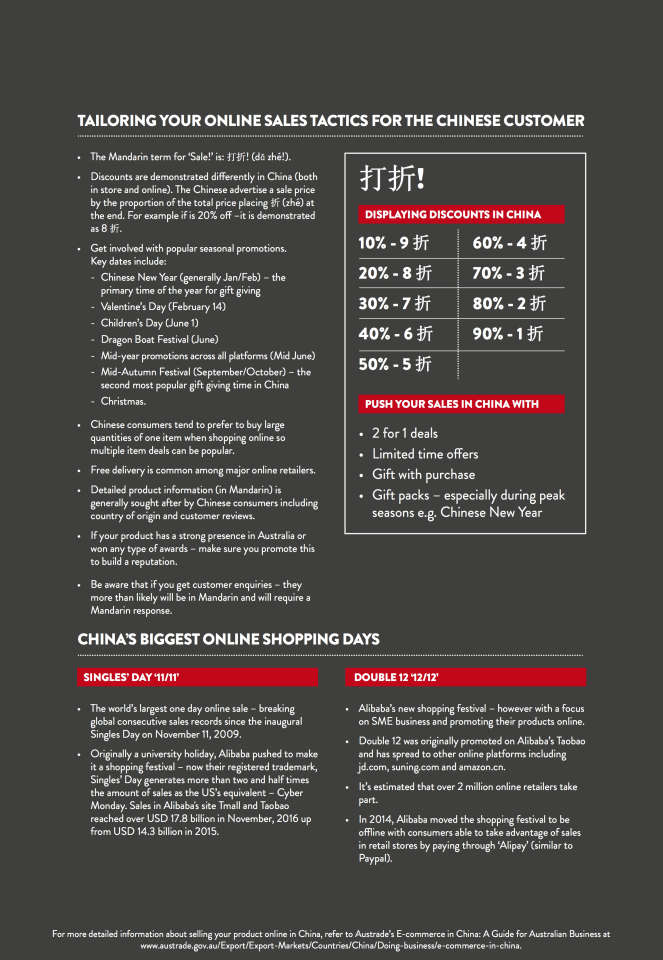

China has the most Internet users in the world today, with over 700 million reached in 2016, more than double the number of Internet users in the US (282 million). China is the world's fastest-growing and largest e-commerce market. China's total online retail sales are expected to hit USD 2.4 trillion by 2020. Popular online purchases include cosmetics, health products, computer hardware and and women's apparel, and mobile sales are increasing.

Keep up-to-date with changing government regulations associated with online sales.

Boston Consulting Group identified that:

Alibaba.com is the largest e-commerce company in China. It dominates the B2B (business to business) market and its Tmall and Taobao websites enjoy the biggest market share of the B2C (business to consumer) and C2C (consumer to consumer) markets respectively. Tmall Global allows foreign businesses to sell online in China. Australia Post has an agreement with Tmall Global to support Australian SMEs selling there. Other Chinese e-commerce companies include Jingdong, Dandang and Yihaodian.

Chinese consumers usually use local search engines, not Google. Many other well-known websites are not available in China, including Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, but there are Chinese equivalents.

Together with the flourishing Chinese ecommerce

industry, China's online payments market is also booming.

Alipay, with over 400 million registered users in 14

countries, is China's leading online payment system

run by the Alibaba Group. Alipay's major domestic

competitor WeChat pay/Tenpay, owned by Tencent, has

also contributed to the robust development of China's

third party payment market.

In particular, QR code scanning through Alipay and WeChat pay mobile apps is considered as a more convenient payment option compared with cash and credit cards, and is currently the most used third party payment method in China.

The Chinese ecommerce market offers immense opportunities but its landscape is very unique. From internet search engines to online payment systems, the Chinese consumer has a preferred way to research and purchase products.

Through Tmall Global and Jingdong Worldwide, Australian businesses can create an online store and sell online without a physical presence in China.

Search engine marketing (SEM) is an essential form of online marketing in China. To ensure Australian products can be found online in mainland China, it is important to customise your SEM efforts to suit China's local search engines such as Baidu or 360, rather than Google. Australian businesses are also encouraged to have a China domain website, which assists your page being picked up on Baidu.

Social media platforms are also a key marketing element in Chinese ecommerce. Instead of Facebook or Twitter however, it is critical to use Chinese social media apps such as WeChat, Weibo and Youku to reach the widest target market.

Two common logistics options used by foreign sellers are the direct business-to-consumer (B2C) option and bonded warehouse (B2B2C) option.

Under the B2C model, foreign businesses warehouse their stock in Australia and deliver products to Chinese customers once they have completed an online purchase.

The B2B2C model involves Australian sellers setting up a warehouse in one of China's cross-border comprehensive pilot zones. Foreign goods are then shipped into China and stored in a warehouse under customs supervision, then delivered directly to purchasers in China.

The two models receive support from the Chinese government and enjoy use of the integrated customs system, which simplifies cross-border trading procedures.

When it comes to setting a recommended retail price (RRP) for cross-border ecommerce, Australian businesses need to consider a wide range of factors that they may not be familiar with.

Conducting a comprehensive market analysis and price comparison within the relevant industries is always fundamental to fixing your retail price. Other factors including logistics costs, ecommerce platform costs and customs duties are also essential considerations in setting a profitable yet competitive retail price.

Understanding and following China's new rules for its cross-border ecommerce industry is critical for Australian businesses. One important rule is that fresh food including fruit, seafood and milk can only be sold through a bonded warehouse zone as these products are subject to stricter quarantine inspection.

In addition, under the Ecommerce Tax Circular, products including infant formula milk powder, infant formula food, food for special medical purposes and health food are also required to follow China's Food Safety Law. In particular, infant formula milk powder and health food that is imported for the first time to China are required to register with China's Food and Drug Administration before 1 January 2018.

Ecommerce is becoming an increasingly effective way to promote and sell your products in overseas markets. Intellectual Property protection however can be challenging. Ecommerce based businesses can easily be affected or paralysed if the company's business name or trade mark is stolen or pirated.

Australian businesses are advised to register their trademarks and domain names at an early stage as the process of securing trademark protection can take from 15 to 24 months in China.

It is always safer to oversee the trademark process yourself rather than delegating this to your distributor. You should also protect your trademark both in English and Chinese, including any alternate local names or colloquialisms referring to the product .

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Making direct contact with buyers and end users is a low-cost, relatively low-risk option but can be difficult Only certain products can be sold directly, including cosmetics, cleaning supplies and small kitchen products.

Some Chinese clients will not do business with a company that has no local presence. Companies in China with successful direct selling strategies tend to employ a high number of direct sales agents.

Seek professional advice if you are considering direct selling: you'll need to understand Chinese tax and import duties. And remember you'll be responsible for everything: market research and marketing, distribution, shipment, warehousing and delivery, customer and after-sales services and order, billing and collection processes.

Australian exporters may sell directly to Chinese retailers or retail chains when consumer products are involved. To do this, you need to travel to China and make contact with retailers, and use direct mail material such as letters, brochures and catalogues. This method generally reduces commissions, reduces travel and reaches the market more effectively. You can also use an agent or distributor to get your products to a retailer.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Franchising is very popular, particularly in the food and beverage industries and in retail and business services. It provides access to local capital and local knowledge of consumer habits, retailing practices and real estate opportunities. Franchising regulations are relatively new and are continually evolving, so seek legal advice before setting up a franchise.

Australian businesses looking to franchise in China must:

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Seek local expertise in marketing and advertising, and be prepared to continually reassess your marketing plan in this fast-changing environment. Be particularly mindful of:

China is really a series of markets, each with thousands of different outlets for goods and a broad mix of channels. Different regions have different tastes. Useful information is available from the Hong Kong Trade Development Council – visit: http://www.hktdc.com/en-buyer/.

Trade shows and exhibitions: Have your sales and product literature and technical specifications translated into Mandarin and take a bilingual representative or interpreter. A senior representative of your business attending can help establish your reputation.

Product and service adaptations: Adapting your product to local regulations, tastes and cultural preferences vastly improves your chances of success.

Brand marketing and advertising: If your company or product name has an embarrassing or negative meaning when translated into Mandarin, customers will flee. Seek professional translation advice.

Symbolism is important in Chinese culture. Colours red and gold and numbers 8, 6 and 9 are considered positive whereas black and white and the numbers 4, 14 and 24 are viewed negatively.

How Chinese characters are written (calligraphy) is important when communicating to a Chinese audience. Note that calligraphy is covered by intellectual property.

Australian businesses should aim to have names with auspicious meanings, such as longevity, good health, luck, happiness and wealth.

Advertising is highly regulated – engage experienced China specialists as advertising laws can be applied inconsistently.

Consider using Chinese-language publications to promote your products and services.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

China has strict rules for product labelling. Labelling requirements vary between two primary product categories – food and beverages (which have to meet regulations of the Food and Safety Law), and non-food and beverage (which have to have China Compulsory Certification).

The inspection of import labels is the responsibility of China Inspection and Quarantine (CIQ) offices at the port of entry. Requirements are complex and often change.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

The Confucian principles of respect for education, authority and age still underpin many business practices. The importance of family and respect for parents is still very apparent, though the significance of the opinions of peers is growing, particularly with the one-child policy generation. The need to belong to and conform to a unit – a family, a political party or an organisation – is a fundamental. In business, people value positions of authority, the maintenance of harmony via saving face, and the feeling of belonging in a workplace.

You'll spend plenty of time building relationships with potential business partners at meetings and, out of hours, at banquets – or even karaoke. Chinese business people prefer to establish a strong relationship before closing a deal and never start a meeting by getting straight to the point about business. Expect to be asked, and to ask questions, about family.

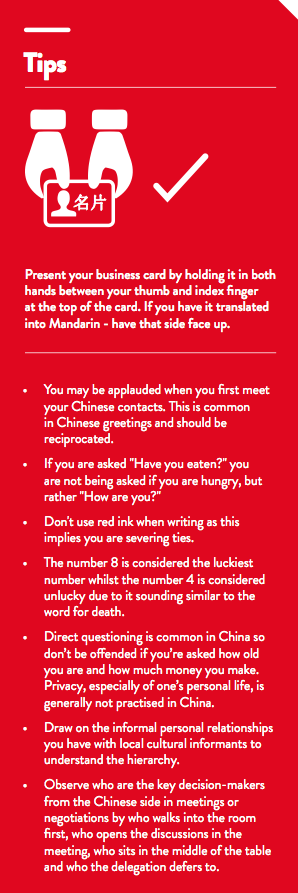

Greetings and titles: A handshake is becoming the standard way to greet men and women in a business setting. Exchange business cards before sitting. Using some simple Mandarin phrases (see Chapter 6) can go a long way.

Be aware that surnames are placed first, e.g. Mr Yao Ming should be addressed as Mr Yao. Married women tend to keep their maiden names, so don't assume that their title is Mrs. If you are introduced to a woman as “Zhen Xiao" it is best to refer to her as Ms Zhen unless otherwise directed.

Business cards: Míng piàn (名片) are essential in Chinese business and must be handled with respect.

Dress code: Conservative professional attire is expected in business settings. Men should generally wear a suit (with tie) and women a business dress or suit with a blouse (not low-cut and, in the case of skirts, not too short). In summer men can wear sports coats with slacks and open-necked shirts. Women should avoid heavy makeup, exposing their backs, shorts and excessive jewellery.

Guanxi: Often translated as “connections", “relationships" or “networks", none of these terms do justice to the fundamental and complex concept of guanxi and its central role in Chinese culture. Guanxi can also be used to describe a network of contacts, which can have a direct impact on conducting business in China. Maintaining open “bureaucratic relationships" can help businesses set up with minimum delays, but also bring challenges. Some legitimate guanxi building may lead to corruption, such as the awarding of a contract to someone in guanxi networks instead of the bidder with the best qualification. Australian businesses can struggle to integrate guanxi into their business practices. The key is to remain diligent and be aware that the guanxi dictates an informal obligation to “return the favour".

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

It's worth investing in business relationships, as they can determine many aspects of commercial life. Age, gender, educational and marital status all impact on the formation of personal and commercial relationships.

General knowledge of China: Relationships can be aided by some knowledge of China and its culture. For example, demonstrating knowledge of Chinese geography when someone tells you where they were born could help them trust you.

Formal introduction: The Chinese prefer to do business with people they have a personal connection with. It can help if you are introduced to a prospective business associate through an intermediary.

Conscious effort: Developing and maintaining relationships will require frequent visits, almost daily communication (preferably CEO/company director to CEO) and plenty of socialising.

Gifts: Giving gifts is an important aspect of Chinese business culture. Overtly Australian gifts such as toy koalas and gifts with your company emblem will be well-received. Give and receive gifts with both hands and don't open them in the presence of the provider. Have gifts available for unexpected meetings.

Avoid giving expensive gifts that will make the receiver feel obliged to reciprocate. Wrap gifts in bright colours such as yellow or red. Don't give sets of four, knives or scissors or use red writing. Also note:Dining and entertainment: You are likely to be invited to dinners and entertainment such as golf, nightclubbing or karaoke. If invited for dinner at a business contact's house, arrive on time, remove shoes before entering and take a gift. At karaoke, almost everyone is expected to sing. Businesswomen attend such events but spouses are not usually included; however, business people may bring their secretaries.

Business is generally not discussed during meals; the focus is on building trust and relationships. Business breakfasts and lunches are becoming more popular, but are seen as less important than dinners. To impress your Chinese counterparts, ask them to dinner. Working lunches are more formal than in Australia.

The Chinese are generous hosts, often putting on banquets to welcome foreign business guests. You should reciprocate near the end of your visit, inviting everyone you've dealt with. Hosts generally pay for dinner or other entertainment, but guests should insist on paying a couple of times before giving in and offering to pay next time. Always arrive exactly on time; arriving early might suggest that you are hungry and could cause loss of face. The guest of honour is always placed at the head of the room facing the door and should be the first to begin eating. Leave some food on your plate during each course to demonstrate your appreciation of the host's generosity.Be aware that:

To find willing partners, Australian businesses need to offer more than just deep pockets. Firms offering technology or know-how may be more attractive. It can also help to offer access to a strong brand or to foreign markets.

Professional advisers and agents can help you find the right partner, by conducting a market analysis of players, meeting stakeholders and officials, and building the relationships necessary to begin discussions.

With alliances come risks, so build trust and communicate regularly. Using Skype or video conferencing, rather than telephone calls, can help develop trust with partners. Ensuring the most senior executive of the Australian company is available to the China partner avoids insult. If this creates difficulty, try giving the individual with the most knowledge on the issues a high-status title.

Rules and regulations can be subject to local variations in interpretation and enforcement. While regulations are introduced centrally in China, enforcement is conducted at the provincial and city level. This means foreign businesses need to cultivate relationships with local government officials.

Research the various government agencies to determine which ones will affect your business interests. Among those likely to play the most important roles are the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM).

For a full list of the main government agencies you're likely to have to deal with in China, and their areas of licensing authority visit (website).

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

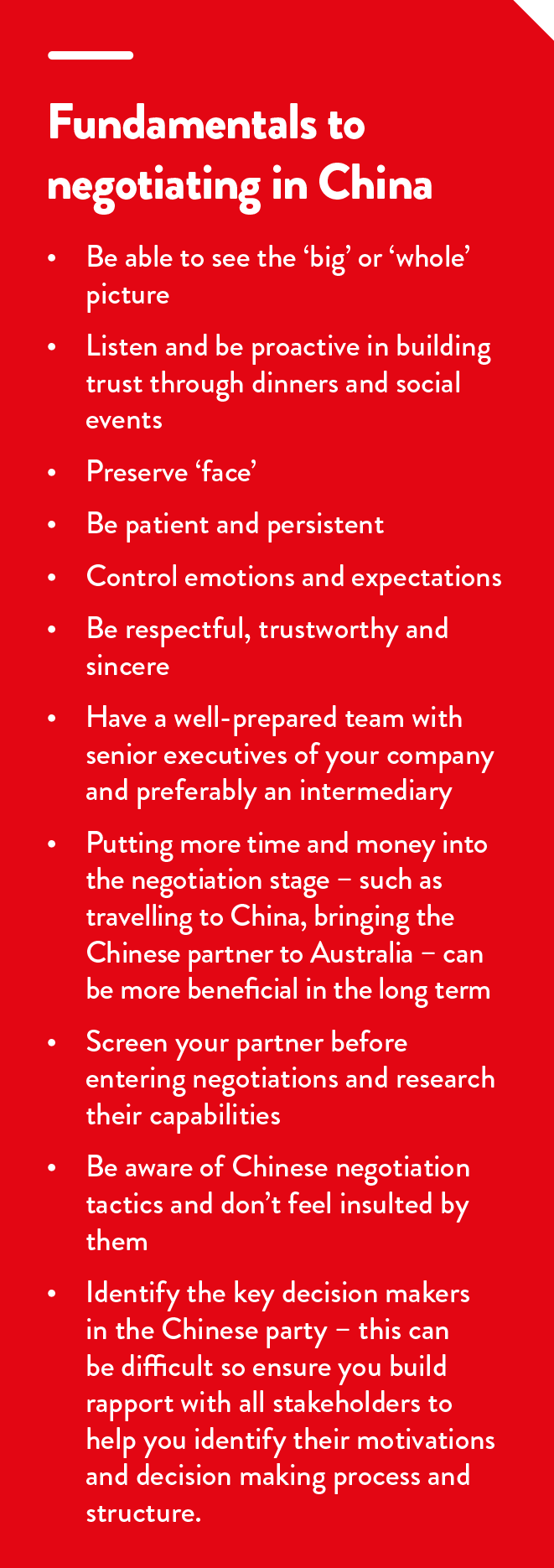

A business that can negotiate well by understanding the 'Chinese style' will have a very strong competitive advantage.

Avoid holiday periods. You may find it difficult to secure meetings with senior company representatives or government officials, and it is not uncommon for the Chinese to only confirm a meeting at the last minute. Send your counterpart as much information in advance as possible, ideally in Mandarin. If you have specific requirements for a meeting room set-up, be sure to tell your hosts in advance.

Most business meetings are held in Mandarin so take an interpreter. Brief them in advance on the meeting's objectives and technical terms that may be used.

Introductions: Never be late. If you are hosting, wait in the meeting room and send a representative to meet the participants outside the building or in the lobby and personally escort them to the room. Assume that the first group member to enter the room is the delegation leader. The senior Chinese person welcomes everyone, then the foreign leader introduces his or her team, and everyone exchanges business cards.

Meetings often start and end with handshakes. If the meeting went well, or if you want to emphasise the importance of the person you're meeting, prolong the handshake. Address the most senior person in the room first and use titles (chairman, director etc). Say your name clearly, and state both the company you work for and your position.

Seating arrangements: At a meeting table, the host will sit at the side of the table facing the door. Each team occupies a single side of the table. The most senior people tend to be seated in the middle of the table. Always sit opposite your Chinese counterpart of similar rank.

At less formal meetings armchairs will be arranged in a horseshoe shape. The Chinese host will take the seat at the left-hand side at the centre of the horseshoe, while other Chinese participants will be seated on the left hand side of the semi-circle. The most senior Australian guest sits on the right-hand side of the centre of the horseshoe with the remaining Australian guests seated to their right hand side. Interpreters normally sit behind the host and chief guest.

Meeting structure: The Chinese begin with small talk before the host introduces the delegations formally. The discussion normally begins with general topics, before turning to more specific topics, followed by the purpose of the meeting. You are expected to reciprocate. Discussions are primarily between the two leaders, although either may elect to include others in the exchange. Lower ranked members do not generally speak unless invited to by the most senior.

When speaking, do not use your index finger or point. Do not interrupt another when they are speaking, or challenge someone directly – it may lead to them losing face. Nods and affirmative utterances during meetings are signals that they are listening and understand what is being said – not agreement.

Ending a meeting: An appreciative remark about the discussion or comment on your busy schedule is a sign the meeting is ending. Gifts may be exchanged at this time and guests leave before the hosts.

Unlike the Western concept of negotiation – which tends to focus on quick deals, task-orientation and designing an effective contract – negotiations in China are a slow-paced, ongoing process founded on developing interpersonal relationships.

Chinese negotiators know foreigners want to finalise everything before returning home, so will prolong meetings to wear the Australian side down. It often can take several meetings and trips to China to reach agreement. Always remain patient and polite.

Some key aspects of the negotiation process include:

Positive indicators that the negotiation is on the right track include: the attendance of higher level Chinese executives, focused questions on specific areas of the deal, the Chinese calling for more meetings, requests to bring in the intermediary, or enquiries on additional options or 'extras' such as overseas trips or training. Remember that even if a contract is signed, the Chinese do not perceive it as binding. Perform due diligence (see section 4.4) as early as possible during the deal process.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Fraud, scams and corruption are ongoing challenges. Due diligence is crucial for interactions with Chinese businesses to protect your own reputation and your business.

Australian individuals and companies can be prosecuted in Australia for bribing foreign officials. Commit to the highest standards of corporate behaviour and familiarise yourself with Australian laws and penalties for bribery.

It's wise to seek professional advice to develop specific due diligence strategies for your particular business. China has a large number of professional services and legal firms that can assist. These range from international audit, tax and advisory specialists to private business consultants.

Begin with a basic background check on potential suppliers. Request basic information on their existing customers and inspect their operations. For an extra level of security, buyers can request audited statements from the supplier or confirm the supplier's registration at the local SAIC.

Check their registration: Get a copy of their business licence, which will be in Mandarin and check that the information on it matches what you already know.

Examine their finances: Professional assistance can be useful here.

Review their references: Consider references of suppliers, customers and even competitors. Learn about their procurement processes, and their guanxi and connections with key official parties.

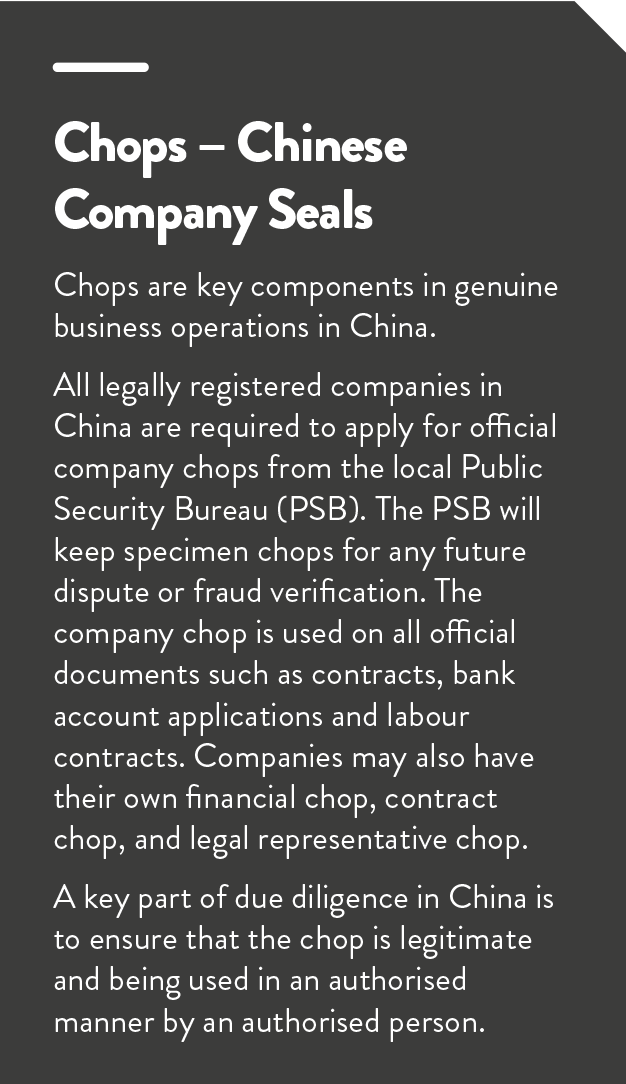

Counterfeiting can include not only fake consumer goods, but money and documentation such as bank confirmations, fapiao (tax receipts) and credit card receipts. These fake documents generally have a fake chop (company seal) on them. Investigate the authenticity of chops by visiting the company or local authorities and asking whether the person holding the seal is the authorised person to sign and stamp the documents in question. A local service provider, a licensed lawyer or a due diligence company can investigate on your behalf. If you're planning to conduct deals in cash, consider measures to minimise your exposure to counterfeit money.Conducting due diligence can help ensure that the companies you are dealing with are actually who they say they are, and identify parasite companies, which rely exclusively on a strong relationship with a governmental decision-maker for its business activities: this level of dependence is risky.

Accountancy standards and procedures are different in China than in Australia. Chinese accounts are unlikely to be audited to the standards routinely expected in Australia, and companies may provide different sets of accounts and financial reports to different parties. It is advisable to use such data with reference to information obtained elsewhere, such as from professional services firms.

Intellectual property (IP) protection is another primary area of concern for Australian businesses. See Chapter 5 for more information.

China has national laws and local laws, which can vary from province to province and city to city. Criminal charges have been laid against Australian businesspeople for activities that are not illegal in Australia – for example, misstating registered capital or having undocumented loans. These charges can result in lengthy prison sentences. If you are unsure about the legality of certain business activities, seek professional legal advice.

China's legal system is complex. It's a good idea to obtain specific legal advice on the terms, nature and content of any contract. Austrade can provide lists of China-based law firms with a track record of working with Australian companies.

If you're entering into a contract to export goods from China, ask to receive small trial shipments to ensure product quality and legitimacy. Austrade suggests employing a good local agent to consolidate, sample and verify goods prior to export.

Ensure the person you are dealing with has the authority to do so by requesting copies of powers of attorney and other corporate authority evidence. Limit your exposure in contracts by conducting a thorough risk analysis. Check your Chinese partner's goals and objectives match yours, set milestones for performance and have an escape strategy for each stage of the project, even though you don't plan to use it. Agree and list the governing law in any documentation.

Dispute resolution: Companies involved in international commercial disputes should seek appropriate legal advice in Australia or overseas. Austrade can provide referrals to legal service providers. There are several international arbitration commissions so seek advice on which is best to use for your particular situation.

Many commercial contracts in China will contain a standard clause stipulating that negotiation should be pursued before other dispute settlement mechanisms. Failure to do this may exacerbate a dispute.

To try to avoid commercial disputes:

Visit www.scamwatch.com.au for suspect schemes that can affect your business here in Australia. If you believe you have been contacted by a scammer, ignore the emails and delete immediately.

Many scams in China target foreigners and foreign businesses. The Canadian Government's Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development has identified the following:

Regardless of the tactic, the scammer's goal is to extract money from foreign companies without providing anything in return.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

China's foreign investment system has evolved considerably in recent years, with many reforms stemming from the country's accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2001. The top three industries for foreign direct investment are manufacturing, real estate and leasing, and commercial services. Every investment project requires specific government approval, with restrictions and regulations varying across industries and regions and subject to regular change.

Foreign investors need to refer to the Investment Catalogue – shorthand for The Foreign Investment Industrial Guidance Catalogue (2011) – which sets out whether industry sectors are encouraged, restricted or prohibited.

More information on the catalogue and the government bodies you'll encounter as you prepare to invest in China can be found (on website).

Finding premises in China can be hard. No foreigner can currently own land in China. Generally, Australian businesses can get land use rights through a WFOE or a JV.

Land and buildings in China are designated industrial, residential or commercial. Requirements for leasing property will depend on the business structure of the venture being set up. For example, WFOEs must have their planned place of business leased prior to submitting an application to establish a business. 'Virtual offices' (effectively, letter boxes) are rarely allowed so the investor may have to rent in the district in which they are registered. Licensed real estate agents can help not only in finding, leasing or buying commercial or residential premises, but also in undertaking registration, sourcing furniture and fittings, and completing installation. Law firms can help with translating lease documents.

The use of serviced offices in China is a good option, especially if you have a limited budget. These often have bilingual secretarial support.

Ensure that the premises and its location are approved for carrying out the type of business proposed. Note that leases generally run for two or three years and can be very difficult to break.

China's legal framework for IP protection meets international standards, though implementation and enforcement are areas of concern.

Formal legal protection of IP rights is needed well before entering the Chinese market. Registering IP rights in China is more expensive and far slower than in Australia: trademarks take 18 months to be granted, design patents six to eight months and copyright recordal procedures three months. Also, China has a first-to-file system requiring no evidence of prior use or ownership, leaving registration of popular foreign marks open to third parties, who register famous marks ahead of the legitimate owner.

Without registering IP rights ahead of entering the Chinese market an Australian business would be unlikely to be able to enforce them later. There are various methods for registering IP, depending on its type. The Australian Government's IP Australia website has detailed information on registration and how to tackle infringements.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Various import duties and taxes, and other import regulations, may apply when exporting goods to China. For Australians exporting to China, tariffs and duties are calculated on the complete shipping value, which includes the cost of the goods, freight and insurance.

Tariffs and import regulations are frequently revised and subject to change without notice. Import regulations also differ by industry and product. Prospective importers should seek professional advice and refer to the appropriate ministerial website for the most up-to-date regulations. These include:

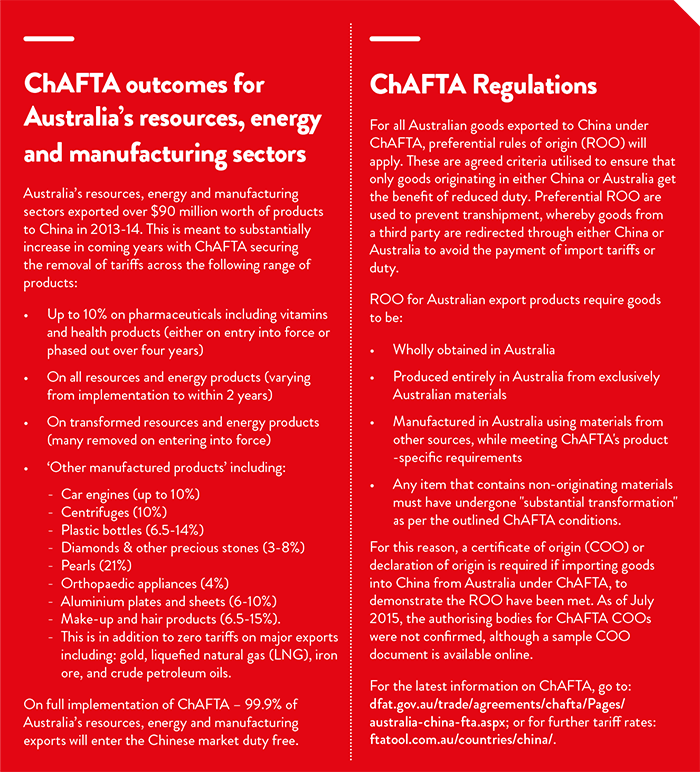

Currently, Australian goods imported into China are subject to standard tariffs. However, once ChAFTA comes into force, many products will be subject to preferential tariff rates.

Customs duties: These may apply to goods imported into China from a country other than Australia. Rates are calculated per unit, or on value.

Additional taxes on imported goods: The main two additional taxes on imported goods are:

One of the biggest opportunities for Australians considering exporting goods to China is in the area of food and beverages.

Regulations around food safety are strict and complex. See (website) for details.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

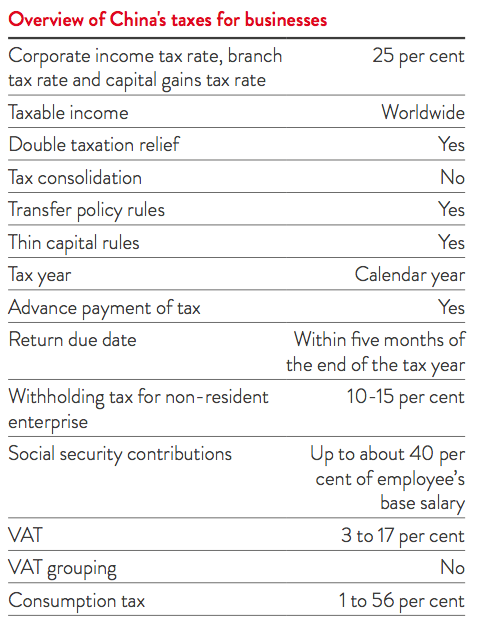

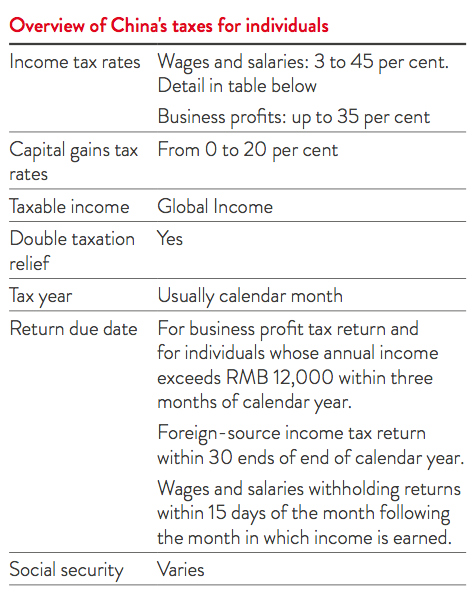

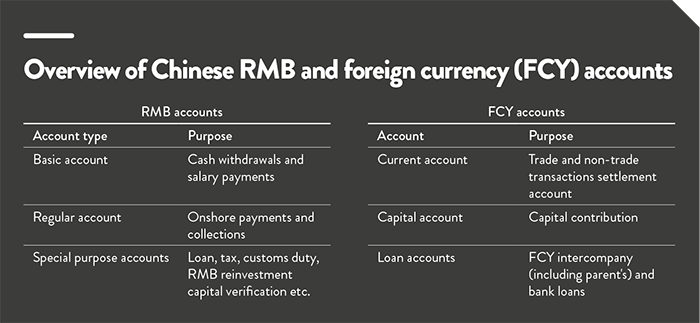

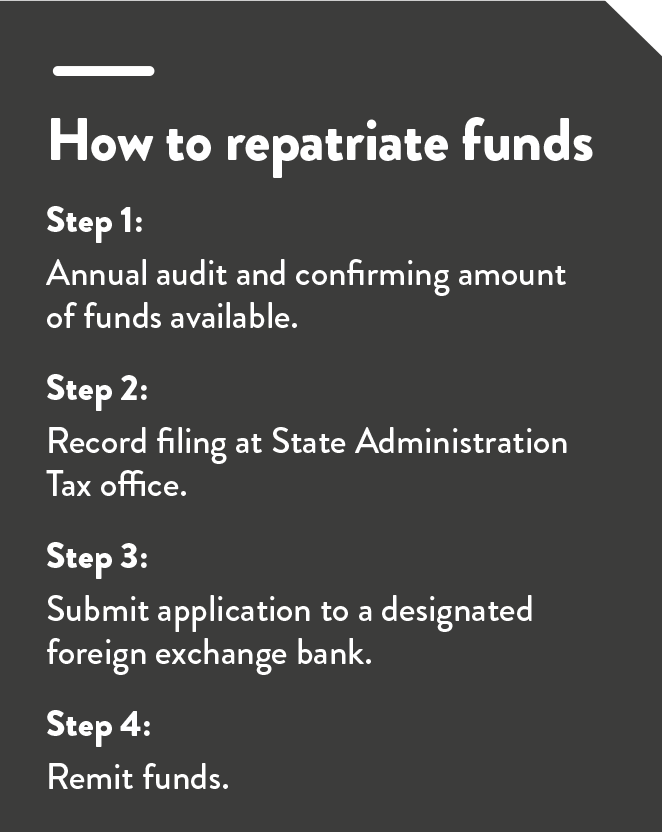

China's taxation system includes a wide range of imposts on businesses and individuals including income taxes, turnover taxes, taxes on property, as well as others such as stamp tax, customs duties, motor vehicle acquisition tax, vehicle and vessel tax, and urban construction and maintenance tax. The laws and regulations which underpin the nation's tax system are currently in a state of transition. In addition, applicable tax laws and policies vary depending on the city and province in which a business is operating.

The tax year in China is the calendar year. Annual tax returns must generally be filed on or before May 31 the following year. Provisional reporting and payments must be made monthly or quarterly, determined by jurisdiction. Provisional payments are usually settled within 15 days of the end of each month/quarter.

More detailed information on taxes is available on (website) but it's recommended you also seek professional advice from firms such as PwC.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

Companies' annual income tax returns and statutory audited financial statements should be filed with local tax authorities within five months of the end of the tax year. The audit has to be conducted by a certified public accounting firm registered in China.

For more information, access the full China Country Starter Pack

You successfully shared the app

https://chinacsp.shareableapps.com/

Tap and hold link above to copy to clipboard.

Are you sure you want to delete this message?

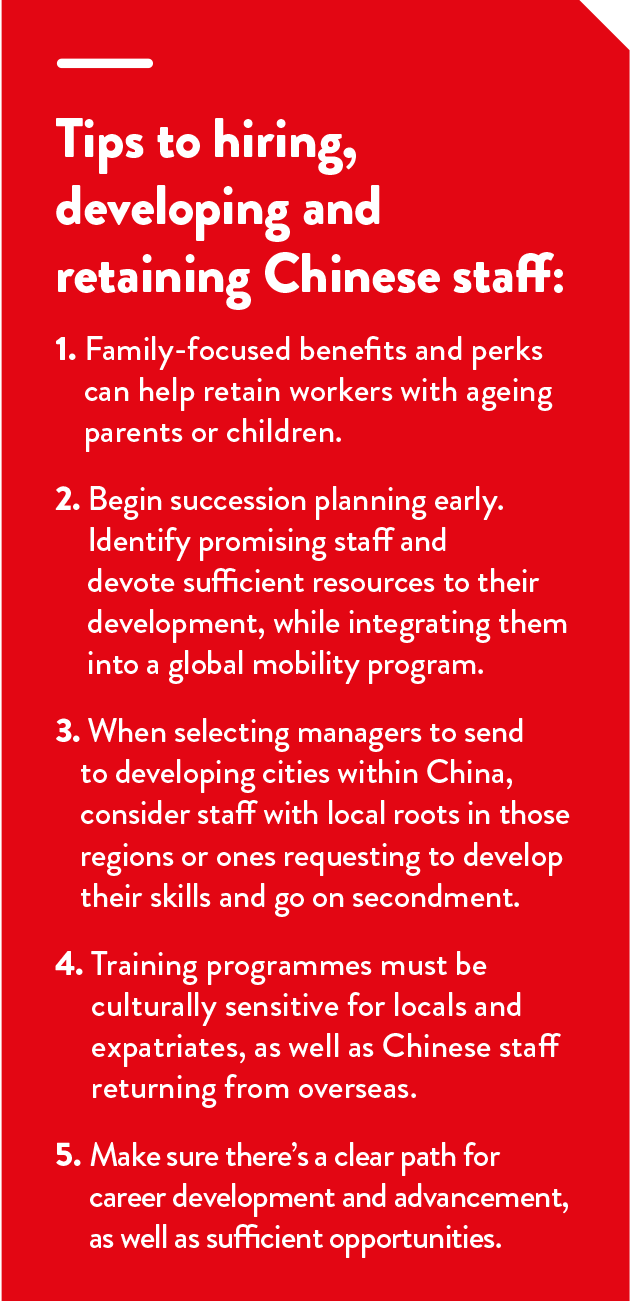

China's labour market is constantly evolving and competition for talent is fierce. Many graduates do not have the business skills needed by large firms and talented workers may be poached by competitors or other industries. Less-educated employees may change jobs for a small pay rise; training and development opportunities will tempt better-educated workers to move.

Chinese managers generally have less experience and knowledge than their international peers: on average, Chinese chief executives are almost 10 years younger than bosses in Europe and the US. Newly-promoted managers often don't have the guidance of experienced senior management, and may leave for higher-paid jobs with less responsibility. There is a limited supply of experienced employees in rural and developing cities, and in the country's interior regions.

Parents get involved in their children's careers and even may complain to the manager if their child is stressed by work.

The Labour Law of the People's Republic of China of 1995, along with the subsequent Employment Contract Law (2008) and other employment-related amendments and rules, underpins employment laws applying to both private and public sectors. Foreign-owned enterprises and joint ventures are similarly covered.

The 2008 legislation essentially encourages employers to enter into contracts with their employees either for non-fixed or long terms, that outline clearly regulations for terminating employment. Amendments introduced in 2013 incorporated, among other things: